- Home

- Rick Boling

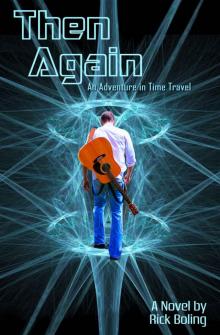

Then Again Page 7

Then Again Read online

Page 7

We had barely made it onto the platform when a window in the curved surface of the car slid up and out of sight to reveal two rows of seats separated by an access space. Each row contained four contoured chairs, and an aisle down the middle split them into sets of two. “Pick a seat,” she said. “The trip will take about ten minutes.”

I chose a seat next to the aisle and waited while the same kind of form fitting-restraints I remembered from Heyoka’s car closed around me. Aurélie sat across from me and pointed to my glass. “You should drink some of that,” she said. “We’ll be accelerating and decelerating rapidly, so there’s going to be some jostling. You’ll be pushed back into the seat a bit, then forward into the restraints as we come to a stop.”

A brief whining sound prodded me into action, and I managed to drink half the whiskey before the window slid closed and I felt myself being pressed into the seat. The G-force increased for about a minute, then let up until it felt like we were floating.

“I supposed this is all part of that CERN thing Heyoka told me about,” I said a little too loudly. Being accustomed to airliners and commuter trains, I’d tried to speak over noise that wasn’t there. In fact, as in the corridor, the silence was almost total, and the acoustics were deader than a sound booth in a recording studio. “It’s some kind of international scientific complex, right?” I said, lowering my voice. “With a big supercollider?”

“Not exactly,” she said. “I mean, you’re right about CERN and the LHC, but not about this being part of it. The lab, as we affectionately call this collection of tunnels, shafts, and underground chambers, is a privately funded research facility, designed by Heyoka, and constructed by a team of Native American technicians.”

“You’ve got to be kidding,” I said. “These shafts and tunnels had to have been cut through solid bedrock. And judging from the distances we’ve traveled so far, the entire thing has to be huge.”

“It is huge, Rix. This tunnel alone is over six kilometers long, and there are several others for delivery of materials and maintenance supplies. The offices and storage areas, back where we left Heyoka, are about the size of an average Holiday Inn, and the central lab structure is perhaps two-thirds the diameter of the Superdome and twice as tall. Surrounding that are several anterooms and research labs and the ecosphere stabilization system, which includes the water and power plants. Finally, there is the computer processing and data center, though that doesn’t take up much room in this dimension.”

“Now you’re losing me,” I said. “If you’re going to start talking about other dimensions, you’ll have to bring things down to my level and go real slow. But tell me something: if this isn’t part of some government-sponsored operation, who financed it? The excavation and construction must have run in the tens of millions. Not to mention the cost of acquiring the rights to build it here.”

“Total cost was over ten billion if you include the political payoffs it took to secure the cooperation of both France and Switzerland. As for who paid for it, that would be Heyoka.”

“Give me a break. I mean he said he’d amassed what some people might think of as a small fortune, but ten billion dollars? I don’t think that qualifies as small. Where would he get that kind of money?”

Before she could answer the car began to shudder like a plane hitting an air pocket. Seeing my alarm, Aurélie reached across the aisle and laid a hand on my arm. “Don’t worry,” she said. “We’re passing under the outer ring of the LHC. The vibration is caused by the interaction of the collider’s magnetic field with our Maglev drive. It'll be over in a second.”

After the vibrations faded I took a moment to gather myself, then said, “Okay. That was … interesting. Now, about the money?”

“Well,” she said, “there’s no real mystery there, although few people know the extent of Heyoka’s fortune or its origins. He’s become a very private person over the past decade, mainly because of the ridicule he’s been held up to by attempting to go public with some of his theories. Plus, he doesn’t want the publicity and invasion of privacy that would result from being known as a multi-billionaire.”

“Multi-billionaire,” I murmured. “So, you’re saying you can’t tell me any more than that?”

“Oh, no. Not at all. He’s told me to be completely open and honest with you, which is quite a compliment, actually. But before we get into that, there’s something you need to understand about Heyoka. As successful as he’s been financially, he doesn’t think of his wealth as anything more than a means to an end. Don’t get the idea he’s obsessed with making money, because he’s not. The only things he’s obsessed with are science, mathematics, and music. And, of course, his privacy. Especially when it comes to this particular project.

“As for where the money came from, Heyoka owns an interest in some of the most profitable corporations in the world, mostly as a result of shared patents for his inventions. Back in the ‘60s and ‘70s he did independent research for a little firm you might have heard of called Intel, coming up with an idea that led to the development of the first commercial microprocessor. Before that he helped Texas Instruments perfect the first integrated circuit. Although he’s never gotten—nor has he asked for—any public credit for these contributions, he did reap the financial benefits, and he used them to make some very shrewd investments in the healthcare and aerospace sectors. Today, he holds patents on several medical devices and a raft of other inventions and processes he developed for various aerospace companies and NASA.”

“Good God,” I said. “How does one man find time to do all that? And what about this ostracism crap? With all those accomplishments, why would he be considered an outcast among his own colleagues?”

“In case you haven’t already figured it out, Heyoka is a genius of the first order, but he’s also a rebel. Not only does he refuse to work as anyone’s employee, his more recent theories have led to negative reactions from many of his scientific brethren. Which is why he decided to retreat into semi-seclusion. He still consults with a few of his more open-minded colleagues, but they wouldn’t dare reveal their association with him and be branded as supporters of his bizarre ideas and unconventional research endeavors.”

“Endeavors?” I said. “You mean there are other screwball experiments going on down here besides messing around with alternate realities and multiverses?”

“Many. We have other divisions working on things like antigravity, cold fusion, quantum teleportation, nucleosynthesis, fuel-cell technology, genetic engineering, and computer consciousness.”

“Right,” I said, still trying to wrap my mind around all this. “So what you’re saying is that he’s, I don’t know, on some other planet intellectually?”

“Metaphorically speaking, he is, but you shouldn’t let that make you think he isn’t a regular guy. Even though he’s accomplished goals few other physicists or mathematicians on the planet have ever dreamt of, some of his greatest loves are simple things like fishing and nature and music. Especially, I might add, the music of one Rix Vaughn.”

“Yeah, so he’s told me. I still don’t get it, though. With his brains and money he could have access to any superstar in the world. So why in the hell would he take an interest in a broken-down old guitar picker like me?”

“That’s a question you’ll have to ask him, and I wouldn’t be so quick to sell yourself short. Heyoka sees something special in you, and the chances of him being mistaken are in the billion-to-one range. Besides, I like your music, too, and I’ve got a collection of recordings that includes the entire discology of every singer-songwriter who ever lived.”

“I guess I should thank you for the compliment,” I said. “But as I’m sure you know I’m way out of my league when it comes to understanding all this tech-speak about quantum physics. He said you were good at explaining things, so …”

“Don’t worry, I plan to do a lot of explaining once we get to the lab where I can use some sensory aids to help you grasp things. As for being out of your

league, I think it’s time you came clean about that and stopped playing dumb. Heyoka told me you’ve been a lay student of science and a reader of SF all your life. Things will go a lot faster if you don’t make me teach you how to add two-and-two, or explain the difference between a leopard and a lepton.”

“There’s a difference?” I said, allowing a smile to crack my lips. “Listen, maybe you’re right about what I know and what I don’t, but you must also be aware that I’m a right brainer, that I think in analog rather than digital terms. When it comes to interpreting mathematical equations I’m about as competent as a retarded groundhog. I could never even learn to sight-read music for Christ’s sake, and I failed every algebra class I took before dropping out of high school.”

“Yes,” she said, “but you’re not stupid. Far from it, actually. Your IQ …”

“I know. I know. My folks made a big deal out of it back when I was a kid. But somehow having a genius IQ never translated into being good at learning stuff, especially when I was a cog in that mind-numbing production line they call school. The thing is, I think and memorize in the abstract. I need symbolic examples, everyday analogies I can relate to tangible things I’m familiar with. I do understand a little about multiple universes and the proposed vibratory aspects of string theory, but only because I can equate them to the indeterminate nature of musical improvisation and the overtones of plucked strings. I have no understanding of the science behind those theories because I’ve never been able to visualize the world of quantum mechanics.”

“I can appreciate those limitations, Rix, and hopefully I’ll be able to explain things visually or metaphorically, using analogies and everyday language. We’ll see about that. But right now you’d better brace yourself for deceleration, or you’re liable to end up with a non-metaphoric puddle of Jack Daniel’s in your lap.

The Lab

After exiting another airlock and negotiating a series of labyrinthian corridors, we ended up in a long, curved passageway dotted on either side with an occasional smooth recess. We passed several of these indentations before Aurélie stopped and turned to face one. A small panel at the side glowed with the letters NIFS.

“This is our NIFS Complex,” she said, as the skin of the recess separated along a previously invisible center line. I followed her into a tear-shaped atrium, from which five evenly spaced hallways split off like arms of a starfish. “The acronym stands for Nonlinear Interdimensional Feedback Studies, but don’t waste your time trying to figure out what that means. I’ll do my best to explain what we’re doing here later.”

We entered the first hallway on the left and walked to the end, where another portal opened into a room that reminded me of an IMAX theater I’d once visited at the Kennedy Space Center. Except for the floor, the room was spherical, and the walls glowed with a milky translucency. Two high-backed desk chairs sat in the center, surrounded by a circular desk with a panoramic computer screen that stretched halfway around. A portion of the desk split away to allow us inside the circle, closing behind us after we entered.

Aurélie motioned for me to sit. “So,” she said, settling into the other chair and spinning around to face me, “what would you like to talk about first?”

I was still carrying my empty glass, and when I held it up, she reached down and pulled out a file drawer. “Sorry,” she said, retrieving a bottle of Jack, “I don’t have any ice in here, but at least you won’t go thirsty.” She poured some of the brown liquid into my glass while I tried to sort through the hundred-or-so questions banging around in my head, one of which occurred to me as I took a tentative sip.

“Before we get into all the technical mumbo-jumbo, I’m curious about this.” I held up the half-filled glass. “To be more specific, why is it that you and Heyoka seem so intent on keeping me supplied with whiskey? Judging from what you know about me, you must be aware that I’m killing myself with this crap, so I’m wondering if you’re trying to hasten my death.”

“No … not at all.” Her hesitation made it clear the question had taken her by surprise, and I watched as her once-confident demeanor faded into nervous confusion. She opened her mouth again, but all she could manage was an exasperated sigh.

“What?” I said. “Doesn’t Heyoka’s order to be open and honest cover the beverages you serve me?”

“It does,” she said, resting the bottle on a knee. “I was going to explain about that, but I wanted to wait until we discussed a few other things first.”

“It’s spiked,” I said, realizing for the first time that the vivid memories, the uncanny sense of traveling back in time, had probably been helped along by a chemical stimulant, most likely an hallucinogen. “You’ve been drugging me.”

“Look, Rix,” she said. “In the first place, we mean you no harm. The concoction we’ve been passing off as Jack Daniel’s is far less harmful than the real thing, while producing a nearly identical kick, complete with simulated hangover symptoms.”

“Concoction,” I said, taking another sip. “Sure does taste like Jack.” I wasn’t worried about being drugged. Besides, it wouldn’t make much sense for them to go to all this trouble just to poison me. “Do you want to explain, or should I keep on drinking until I’m comatose and don’t give a shit anymore?”

“You could drink a couple of gallons without becoming comatose,” she said. “In fact, you’d probably drown before there were any adverse health effects. The host beverage is a nontoxic simulacrum of aged Tennessee whiskey, with a simple alkaloid base, some artificial flavors and coloring, and a tiny infusion of psychoactive compounds designed to mimic the high of alcohol. The neuroimaging enhancement—the chemical matrix that stimulates and clarifies memory—is something that evolved out of Heyoka’s efforts to duplicate changes in the brain that occur during so-called spiritual experiences. And you should know that the minuscule quantities you’ve been ingesting have only provided a preliminary introduction to some pretty amazing things. The next stage, which we refer to as Stage Two, will, if you chose to continue, involve participatory experiences you won’t be able to tell from the real thing.”

“Been there, done that,” I said with a smile. “Sounds a lot like LSD or Ecstasy.”

“There’s no comparison,” she said. “Those synthetics cause hallucinations, dream states that warp reality. This, on the other hand,”—she held up the bottle—“stimulates real memories, things that have actually happened, with no alteration whatsoever. You may have forgotten details of your past on a conscious level, but all the information—the raw data—remains stored in your subconscious. And under the right circumstances that data can be reconstituted into clear and precise memories. Several cultures have learned how to access these subconscious reserves through physical deprivation, meditation, or the ingestion of certain plant materials, sometimes even going back in history to retrieve what might be called communal or collective memories. But until now no one has come up with a way to duplicate such processes in the lab.”

“Far out,” I said, sniffing the glass. “What’s in it, exactly?”

“That’s hard to explain unless you happen to be familiar with a branch of science called supramolecular chemistry. The original formulation has been reintegrated at the molecular level into something that would be unrecognizable to your average chemist. If I were to go back to its chemical origins, I could point to ingredients like acetylcholine, scopolamine, salvinorin A, sodium thiopental, mescaline, nicotine, and a few other odds and ends. But that has little to do with the formula in its present state. The algorithms evolved from a breakdown of reactions in the brain that result from some of those chemical compounds working in concert with activities like fasting, self-induced pain, yoga, thermal extremes, and a myriad of other physical and environmental influences.”

“Doesn’t sound like much fun,” I said. “Pain, starvation, body contortions? Not exactly my cup of tea.”

“You’re missing the point, Rix. What Heyoka’s been able to do is duplicate these effects with

out the discomfort, specifically so he could work with other subjects in a laboratory setting. At first this only allowed for observation, but recently he’s managed to expand the process, combining it with some non-chemical influences that enhance the effects to allow for benign participation. That is, re-experiencing episodes without being able to alter them.”

“So, that’s what’s been happening to me?”

“To some extent, yes,” she said, turning back to the computer desk. “Although you have yet to experience the full participatory iteration of the process. That will come in Stage Two, if you’re willing to move on.” She moved her fingers over the desk as if typing on an invisible keyboard, and the milky surface of the sphere that surrounded us came alive, resolving into an animated image of me and my dad strolling down a hospital hall. There was no sound, but the wrap-around visuals were astonishingly realistic.

“These projections will give you a two-dimensional preview of what you will see in much more vivid detail during the first phase of Stage Two.”

Dad and I were standing in the coffee shop after he’d finished his morning rounds. Then the scene dissolved into another, this one of me at age sixteen, sitting in my ‘55 Thunderbird with Susan Wilson. I remembered the moment well, since it was the night I finally talked her into having sex. I watched while we got out of the car and spread a blanket on the ground, then as we were about to lie down, the image faded and the sphere went blank.

“I think we’d better stop that one there,” Aurélie said with a chuckle as the walls began to glow with that milky light.

I shook the memory from my mind and leaned forward in the chair. “What you’re saying is that I can pick and choose the moments in time I want, then relive them as if I’m there again?”

Then Again

Then Again